STORIES & NEWS

Discover the stories behind our collaborations with our makers and other creatives.

STORIES & NEWS

SOLLIP

We were so pleased to welcome Woongchul Park and Bomee Ki, the husband-and-wife team of the Michelin-starred Sollip. Their restaurant features JaeJun’s ceramics within a carefully curated collection of tableware and craft by contemporary Korean makers. Sollip’s approach, shaped by European training, London influences and Korean heritage, shares the same thoughtful making and cultural resonance found in JaeJun’s practice.

JaeJun moved to the UK eight years ago on a talent visa, and Flow presented one of his first exhibitions when he began his career here. We are grateful to now host his final solo show as a UK-based maker before he returns to Korea next year, and to be able to share his work with you both in the gallery and now online.

Thank you to Woongchul and Bomee for marking Thursday's opening as a special evening with their canapés.

_

Captured below are two of the canapés prepared for the opening:

BEEF TARTARE

Highland Wagyu, Aged Gochujang, Daikon Jangajji

GAMTAE SABLE

Mornay Sauce, Duckett’s Caerphilly, Dashima

EDMUND DE WAAL at Kettle's Yard

Edmund de Waal came to know Kettle’s Yard while studying English at Trinity Hall in the mid ’80s.

As a potter and a writer about ceramics, de Waal has long reflected on how pots have been presented and perceived. Using the variety of spaces in the gallery and extending into the house with its permanent collection, de Waal installed a series of installations, many of them made specially for the exhibition. The first, ‘A Change in the Weather’, offered the visitor a pot for each day of the year. Further on, there were pots in a skylight, on shelves and in boxes, and running along the street-front window sill. In the last space, we were enticed to glimpse into a room – a Wunderkammer – lined and stacked with 342 plates. In the house, smaller installations, such as ‘Ghost’ replaced the normal pots and found their way into bookshelves and cupboards.

The exhibition was organised with the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, where it later travelled to. It was grant-aided through the Arts Council England Lottery Fund and by the University of Westminster.

- Text & images courtesy of Kettles Yard

De Waal collaborated with architectural photographer Helene Binet, on a series of large plates documenting these installations. Flow is very pleased to present the edition of 'A Change in the Weather,' Digital C type print, from this exhibition. The first edition has its home above the desk at Flow, and at this time of year it just catches the afternoon sunlight.

Helene Binet is a Swiss and French internationally acclaimed photographer based in London, who has captured de Waal's installations and the spaces in which his work is shown, including his studio and exhibition venues.

KETTLE'S YARD

Jim and Helen Ede created in their home a new approach to sharing art - a place where objects and beauty were woven into the ordinary textures of everyday life. There was no hierarchy; a grouping of stones would be as carefully placed as a painting.

Kettle’s Yard, as Jim Ede described, was “a space, an ambience, a home.” Every detail was attended to with care - the light, the quiet, the thoughtful placement of each object - so that visitors might feel at ease and experience a living connection to art. “I used to like to feel,” he wrote, “that each newcomer could feel the first to enter in upon that quiet.”

"It was while I was abroad in 1954 that I found myself first dreaming of the idea of somehow creating a living place where works of art could be enjoyed, inherent to the domestic setting, where young people could be at home unhampered by the greater austerity of the museum or public art gallery and where an informality might infuse and underlings informality. I wanted, in a modest way, to use the inspiration I had had from beautiful interiors, houses of leisured elegance, and to combine it with the joy I had felt in individual works seen in museums and with the all embracing delight I had experienced in nature, in stones, in flowers, in people."

This celebration of creativity, material, and beauty as part of the flow of daily life, continues to guide Flow Gallery.

PAUL PHILP - A Studio Visit

Recently, I had the privilege of visiting the home & studio of British ceramic artist Paul Philp, in Bath. Studio and living space blended under his natural palette and ceramic works bordered every room. Pieces in Alabaster, timber and a new exploration in cast & patinated bronze, also showed his forms spreading through mediums.

His influences are both architectural and organic: Japanese Minka architecture, tribal and ancient art, and forms found in nature. During our visit, he spoke about his early life - of building a home in stone by hand, and living remotely off the land - a reflection of his connection to materials.

Philp’s ceramic practice has evolved over 50 years. His works are largely hand built - fired multiple times with thin layers of slip, organic materials and glazes which create rugged surfaces that feel elemental. The volcanic skins recall the raw geology of clay, yet the forms have an architectural elegance that feels out of time.

There is a connection between the work and the space and it was a moving experience to see it in context.

KWAK KYUNG-TAE - An Interview

What first drew you to working in Onggi (옹기) and Buncheong (분청)?

I first encountered Onggi in the spring of 1993 during my university’s annual ceramics wheel-throwing tournament. That morning began with a demonstration by an elder Onggi master. With striking ease and confidence, he stretched, stacked, and rhythmically paddled the clay into a massive, beautifully proportioned vessel. His movements were fluid yet grounded, rooted in a deep understanding of material, tradition and time.

I was completely transfixed. So much so that I nearly missed my time to compete. But in truth, the competition faded in importance. What stayed with me was the profound presence of that vessel and the quiet authority of the hands that shaped it.

That moment marked the beginning of a long journey for me. Onggi was not just a form or technique; it was a way of being in dialogue with the earth, with history, and with the body. It stirred something elemental in me – a respect for raw clay, a fascination with physical process, and a desire to root my practice in something honest and enduring.

Traditionally, buncheong is celebrated for its clean, white surface; an elegant "makeup" applied to clay, as it’s often described in Korean. But my approach to buncheong departs from that classical ideal. I don’t seek purity or perfection in whiteness; instead I treat the white slip as a blank canvas, a starting point for something more elemental.

When I paint on the surface, I am not only applying imagery. Rather, I am initiating a dialogue between clay, slip, and fire. In the reduction kiln, iron in the clay body interacts with the whiteness of the slip, creating soft blooms of pink, shadowy grays, and sometimes deep, unexpected hues. These iron blooms are unpredictable; formed not by control, but by surrendering to the alchemy of heat and time.

What first drew me to buncheong was this tension between refinement and rawness. Beneath the surface of tradition, I found space for spontaneity, contrast, and elemental transformation. The fire doesn’t just finish the work - it reveals it. My buncheong is not an act of covering, but one of uncovering; not a mask, but a mirror of process and material truth.

How has your understanding of or relationship with clay evolved over the years?

My relationship with clay has shifted over time, but the presence of clay has remained steady. As a child, a creek ran in front of my home and beside it, a patch of soft, white clay. I spent hours using this wild clay to transform my imagination into form. It was quiet, instinctive, and free.

As I grew older, clay became more than a material. It became my profession, my teacher, and a source of discipline and discovery. As it taught me, I slowly built understanding through repetition and attention.

Now, clay is a companion. We’ve developed a mutual trust. It continues to challenge and teach me, but with a sense of familiarity. What began as play has become a lifelong relationship, one that still evolves with each piece I make.

Your work often involves spontaneous marks and gestural brushwork. How do you balance instinct and intention while making?

What may appear spontaneous on the surface is, in truth, grounded in deep intention. For me, instinct is not separate from knowledge. It lives in the body as tacit understanding, shaped by decades of working with clay, fire, and brush. Listening to the subtle shifts in iron in the clay, the slip, the fire, and how they respond to one another.

The true skill lies in making the mark feel effortless, while knowing it is supported by discipline. In that space between intention and instinct, something honest and alive can surface.

Can you describe the physical and emotional experience of working on your large vessels?

Forming a large vessel requires all the muscles, nerves, and breath in my body to become one. A rhythmic movement emerges from my body to tell a story. To viewers, my hand movement may appear to be the main focus, but during the making process I breathe in relationship with my tacit knowledge within my body, creating rhythm and encountering it. In other words, my body, breath, and emotions from a relationship together, and through this unity, the vessel is ultimately completed.

How does minimalism or restraint play a role in your work?

When I apply buncheong, I leave marks with both brush and hand, but I don’t try to resolve or control everything. Through my tacit knowledge, I know when it is time to stop. The remaining space on the clay, the traces of the brush, and even the rhythm of my breath tell a richer story and so I restrain my movements and breathing.

This means I accept the outcomes that arise from the interplay between gesture, breath, material qualities, and process. That acceptance is what I consider my form of minimalism.

What are your favourite tools and processes when making?

My favorite tool is my own hand, an extension of my body. It is a tool shaped by time and experience, refined through years of practice. Over time, my hand has become so familiar with the material that it now intuitively determines both the beginning and the end of a piece.

What does it mean to you to share this cultural tradition with a global audience?

For me, sharing tradition is not simply about teaching the past. It is about sharing lived experience. It involves communicating traditional techniques while also offering a space to reinterpret these through a contemporary lens.

In countless demonstrations and classes, people engage not just with words, but with the process itself. Through Korean traditional techniques, they come to recognise their own forms of knowledge, ones they may not have been aware of before. In this way, I see the transmission of. Korean traditional culture not as a visual exchange, but as a tactile and direct experience.

Are there any pieces in this show that hold particular significance for you?

The byeongpung series is a form of ceramic painting where the canvas is made from clay. During the Joseon Dynasty, byeongpung could be found in palaces and noble homes. These culturally-significant folding screens bore a series of artworks, typically created in ink on paper mounted on silk. These artworks also served functional purposes in Korean architecture as room dividers.

For this series, rather than pursuing a flat, two-dimensional painting, I build up thickness to create a sculptural, three-dimensional effect. On top of this textured surface, the interplay of the gestural brush marks and iron blooms abstractly echo the tradition of jingyeong sansuhwa (진경산수화 - Korean landscape painting).

Much like byeongpung, these works move beyond the function of a traditional hanging painting. Each panel is pierced with holes at the top, giving them practical use and transforming them into abstract ceramic vessels with painterly qualities, rather than merely wall-mounted paintings. Two of the original six panels will be on display.

THE TACTILE HOME

A curation in ceramic, enamelled metal & Reed

Set against the tactile backdrop of timber, concrete and brick, this collection explores craft rooted in materiality. Ceramics, woven fibres and enamelled metal in muted tones, coexist gently.

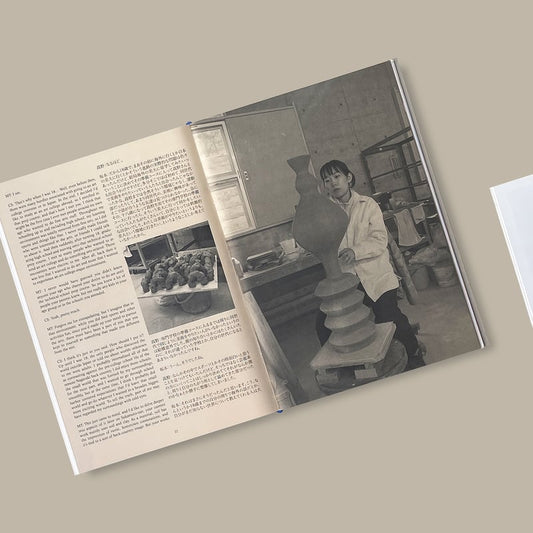

CHINOKO SAKAMOTO - A Solo Show

Flow is pleased to announce our upcoming exhibition - our second solo presentation of Japanese artist Chinoko Sakamoto’s ceramic sculptures.

Now based inNagasaki after a period of study inLondon , Chinoko draws from both cultural contexts. The quietude of rural Japan, rich in nature, and the contrasting architecture of cities, inform her sense of form and scale.

Ahead of the exhibition, Chinoko told us more about her practice and the work she has made for Flow :On Clay -

“When I was studying sculpture at university, I had no idea what I was actually capable of making. I was collecting ideas and interests, trying to figure things out, but when it came to the point of creating something tangible, I felt completely stuck.

It was during a university workshop that I first encountered clay, and somehow, working with it felt incredibly natural. It was as if the clay itself was guiding me, helping me to create something. That feeling drew me in straight away—I was completely absorbed.”

On Influence -

“In everyday life, all sorts of images are stored in my mind—they’re scattered and unorganised. But when I begin by drawing simple ideas in my sketchbook, I extract only the elements I feel like using at that moment. It might be a sense of volume, a shadow, a texture, or a pattern—whatever stands out. From there, I start to abstract those elements.

When it comes to actually working with clay, I look closely at the developing piece in front of me and make decisions—especially about proportions—as I move towards completing the work.”

On Place -

“When I was in London, I think I was quite powerless and ordinary as a student. There was the language barrier, of course, but more than that, I felt empty inside. Still, in that loneliness, art became a real source of support for me. I made a point of observing everything around me closely, struggling to absorb it all and turn it into something that could sustain me.

Nagasaki , where I’m based now, is a rural area rich in nature. It’s a place where I can really focus on making, with plenty of space to work. But I also make a conscious effort to travel elsewhere from time to time, to gain new inspiration.”

On Process -

“Basically, I build up the clay by hand, smoothing and stretching it with my fingers as I shape the form. For finishing the rim, I usually either smooth it with my fingertips or use a thin wooden tool.

When I want to carve more detailed parts, I use a metal scraper, and then refine the surface afterwards with a wooden tool.”

On Surface -

“When I first started making, I found it really difficult to match form with glaze. Even when I felt I’d created an interesting shape, applying the glaze sometimes seemed to take away from what made it special. I struggled to figure out what kind of glaze would suit the organic forms I was making—it felt like chasing clouds. I just kept testing, over and over.

One day, I was watching a film of Lucie Rie working in her studio. I saw her brushing slip onto the surface, then scratching through it, and layering glaze on top. Suddenly it all made sense—that’s how she had been using the slips I’d seen mentioned in her books.

That moment clicked something into place for me. I went to the library, looked up different slip recipes, began testing them, and eventually started using them myself. When I returned to Japan, the raw materials were different, so even with the same recipes, I had to start from scratch with the glazes. But after enough testing, I gradually developed a kind of instinct—I could feel when something was right.”

On Scale -

“In recent years, working on large-scale pieces—some even taller than myself—has had a significant impact on my overall practice. Since starting to make larger pieces, I feel that my approach to smaller works has shifted as well. It’s as if I can now see the whole form more clearly—my perception of three-dimensional shapes has broadened in a more abstract and spatial way.

I’ve also become more conscious of the space that the work creates—not just the form as a single, unified object, but also pieces composed of multiple parts that seem to expand or reach out into the surrounding space.”Photography byIsobel Napier

The Texture of Glass with JOCHEN HOLZ

We recently visited the North London studio of glass artist Jochen Holz, to film the making of his latest series of textured glass tableware for Flow.

Jochen has an intuitive and spontaneous approach to lampworking, and this collection explores the potential tactility of glass.

CÉCILE DALADIER - 'Pique-Fleurs' - A New Ceramic Collection

Shaped in her rural studio in Drôme, France, her Pique-Fleurs honour what is humble: a wildflower, a pool of water, the eloquence of the smallest things.The vessels are designed not for grand bouquets but for the singular presence of a flower. As she describes, each piece becomes a collaboration:“You bring your own personal interpretation... the Pique-Fleurs is a kind of instrument, and you are playing it in your own way.”Cécile’s hand-formed vessels are wood-fired in her home-made kiln and smoked with fallen leaves, herbs and dried grasses gathered from her garden.

We look forward to sharing this collection with you.

Cécile Daladier’s Pique-Fleurs are now available to view online and at the Gallery.“A few flowers, a little water, in a little enamelled earth, can move us.”

- Cécile DaladierStudio photography by Iinsey Rendel

Product photography by Isobel Napier

Elemental Forms - LAURA NGYOU in Her Somerset Studio

On a recent visit to Somerset, I spent the day with jewellery artist Laura Ngyou, filming her in her studio - a lovingly built shepherd’s hut nestled in her garden, surrounded by birdsong and greenery. Watching her work, you can see that Laura's creative process is as intricate and organic as her work.

Laura’s pieces are born from a fascination with miniature natural worlds - imagined seascapes, coral structures, crystalline growths, and botanical fragments. Rather than drawing from a single source, her work evolves from an amalgamation of many memories shaped by travel, nature, and intuitive exploration.

“I’ve always had a preoccupation with the sea and marine life,” she explained, describing the lasting impression of scuba diving expeditions in Fiji and Borneo. “These trips to this day have left me completely spellbound - being part of that other world, having close encounters with manta rays, hammerhead sharks, turtles and the most exquisite coral and fish.”

In her studio, this sense of wonder is translated through constant experimentation. “This involves the melting, hammering and manipulation of metal, until I reach a point where certain forms or textures are created that evoke a memory or feeling, for example of a rock formation, seed pod or plant growth pattern.”

Gemstones, too, play a central role - sometimes initiating a design, sometimes patiently waiting in her collection for the right moment. Recently, she’s been drawn to stones like tourmaline and aquamarine, whose long crystalline forms echo the organic lines she crafts in metal.“Moving to Somerset has definitely slowed my pace of life, allowing me to reflect, appreciate and really access what is happening moment by moment. It has made my experience of living and working more conscious. I am incredibly privileged to have been allowed this space in such a beautiful environment, waking up to and surrounded by trees, plants and the sound of birds every day."

- Larua NgyouLaura embraces ambiguity in her work, and rarely creates directly from life. “I hardly ever sketch or copy. Instead, it’s a memory or a feeling I chase - an impression of a natural object that’s slowly abstracted in the making.” Her creations often blur the line between plant, coral, fungi or mineral - objects that seem both ancient and otherworldly.

Her process infuses each element with organic character. “Gold has this magical warmth and malleability I love. And recently I have been drawn to stones that naturally occur in very long crystalline forms recently, like tourmaline and aquamarine, as they suit the linear forms of the metal samples I have created through melting and experimental casting.”

Despite the intricacy of her jewellery, her tools remain simple. “My soldering torch, a few pliers, my files and saw - they’ve all become like extensions of my hands. I’m preoccupied with finding low-tech ways to manipulate metal, to let it form itself into something abstract and unexpected.”Since relocating from London to Somerset, Laura’s pace of life and creativity has shifted. “There’s a deeper stillness here. I’m more conscious of each moment, more connected to the environment around me.”

Her shepherd’s hut studio is a reflection of that change; a peaceful, light-filled space filled with collected stones, shells, and fragments of nature. “It has been a huge shift for me to move in to my new studio in my garden, that was built with love and care by my partnerRob who is a cabinet maker. It’s a special place, which allows me even more space to dream, work and experiment, surrounded by many of the natural objects and materials I find so inspirational.”

Looking forward, Laura hinted at future projects, including larger sculptural pieces inspired by tree burrs. “I hope (they) will surface one day when I can tear myself away from making jewellery!”

Her ability to blur boundaries between the real and the imagined brings narrative to even the smallest of forms.

Thank you to Laura for inviting us into her studio and sharing some of her processes with us.

Photography, videography & interview by Isobel Napier

On the Square with IRENIE STUDIO

Join us at 9 De Beauvoir Square with interior designer Irenie Cossey - a whimsical show space for craft, design & storytelling.

Dublin-born interior designer and curator Irenie Cossey, recently invited us inside her latest project at 9 De Beauvoir Square. Working in collaboration with makers and designers,Irenie has reimagined this once-abandoned house in Hackney, as a temporary exhibition space and design experiment.

By inviting artists to respond to the space - its history, its materials and its shifting light - she has transformed the home into a platform for contemporary craft and creative friendship. The history of the building is woven into curtains and echoed in blown glass; craftsmanship becomes storytelling.

On the Square features Jochen Holz andMichael Murphy (Muck), whose work will be showcased at Flow this year, alongside many other makers that we’ve had the pleasure of discovering. One of our favourite moments to emerge is Irenie’s poetic collaboration with Irish glass manufacturer J. Hill’s Standard - a studio focused on evolving the heritage of hand-made glass in Ireland.

A glass milk bottle unearthed during the house’s renovation became the starting point for a new series of glass forms. Drawing on the dreamlike spirit ofAlice in Wonderland that weaves throughout the project, they co-created the Mad Chatter Vessels - a joyful quartet of sculptural pieces that play with scale, silhouette, and the animated interplay between objects. These vessels are pourers, holders, and storytellers.

‘They echo the shape of their buried ancestor, each one a reminder that memory lives in material, and every good story deserves a bottle.’

- Irenie Cossey

We look forward to sharing these pieces with you at Flow soon.

It was also lovely to see the work of Irish woodworker and sculptorMichael Murphy (Muck). Above is his piece for Irene’s space - The Upside Down Collection - made from fallen Irish Oak in collaboration with Kasia Kempa, Flavia Bränle and Irenie.

‘The collection grew out of conversations, studio visits and exchanges of drawings…Taking its name from the Irish Gaelic for ‘upside down’, Bunoscionn evokes the sense of a piece of furniture coming to life - even when flipped over and rested on a table. Channeling the physical memory of chairs turned over to make space for sweeping the floor, for dancing, and for looking at life slightly askew, the Shaker brooms were designed to complete the story in a physical way.’

Throughout the house On the Square’s design partners -Domus, Kvadrat and Fenwick & Tilbrook - showcase their tiles, fabrics and paints. Five chairs designed byRobin Day in the 1950s have been reupholstered in deadstock Kvadrat fabrics byStow Studio. Diamond-patterned tiled floors are inspired by the diamond window panes. The Rosa Red paint in the hall, made by Norfolk-based Fenwick & Tilbrook, references a rose bush in De Beauvoir Square.

Each room at On the Square speaks in layers, as makers respond to the building. Textiles salvaged from the home’s original furnishings have been reimagined into delicate, handwoven curtains by Tomoyo Tsurumi. In another room, Eva the Weaver, in collaboration with The Tweed Project, transforms offcuts of Kvadrat fabrics into textural blankets.

Our thanks to Irenie for inviting us into her world.

Photography by Isobel Napier Portrait by Ellen Christina Hancock

ARKET | Takashi Tsushima

We’re pleased to welcome a new collection of ceramic plates by Japanese illustrator and painter Takashi Tsushima to the gallery.

Based in Fukuoka, Tsushima is known for his whimsical visual language—his work blending soft, fluid lines with playful animal motifs. His distinctive style has found expression across a variety of media, from ceramics to textiles, and we’re pleased to share a short film below, kindly provided by ARKET, that offers a glimpse into his world and creative process. The video was produced as part of their collaboration, in which Tsushima illustrated a series of designs for a collection of woven blankets.

A special thank you to ARKET for allowing us to feature this beautiful piece.

“I was born and raised in Fukuoka, and I don’t travel, so I have lived here my whole life. It’s a very compact and convenient city. With a bicycle, we can go both to urban areas, the mountains, or the ocean. … People look friendly and cheerful, and many of my friends are living close to me. I feel comfortable and happy in Fukuoka.”

- Takashi Tsushima

This new collection of hand-drawn ceramic plates beautifully demonstrates his distinctive style, with a semi-transparent quality reminiscent of watercolour painting. Each plate is unique, capturing the charm of his expressive linework with animal and floral motifs.

Tsushima’s approach reflects his belief in the interconnectedness of life: that animals, plants, and people exist in harmony. While his work has been

“I’m not sure I can call myself an artist,” he says. “I never thought of becoming an artist, but I’ve loved drawing since I was a child. It was just a thing I could do... I’ve longed for working in relation to drawing, and for living with drawing. And here I am.”

Playful and soulful, these pieces are not only functional ceramics, but little moments of storytelling.

Photography & videography courtesy of ARKET

Studio Visit with GREG KENT

Omega – the end of the line, and a transition to something new.

In his show at Flow Gallery, Greg Kent presents his oak sculptures, which capture the dichotomy of nature’s fragility and strength. His technique of turning and sandblasting oak, a process first developed by French woodturnerPascal Oudet, reveals the intricate, organic patterns formed by the tree’s growth.

“Turning wood is like uncovering buried treasure as the wood reveals its history, and its struggles. This is manifest in the growth rings, grain patterns and colours. I am interested in the beauty of the wood and by working with wood I want to tell its story and use it to explore narratives.”

“For me, wood and trees are a fundamental part of our existence. They have sustained us in so many ways including: fire, building materials, tools, water storage, furniture and paper. Crucially, they provide us with oxygen and remove carbon from the atmosphere. Woodturning provides an opportunity to give wood another existence rather than being turned into firewood.

I work hard to collect wood from local tree surgeons that would have been used as fire wood. The wood is then 'turned green', this means whilst it is still wet. The wood is turned to a thickness of 2mm and allowed to dry. When dry the wood is sandblasted. This process removes the softer spring growth, revealing fine, textured patterns unique to each piece. This can only be done with oak which has medullary rays which go across the growth rings. This involves combining both wood turning and sculpting. What is produced, in my view, is fine art created by nature, and revealed by a craftsman.”

“The Omega exhibition represents a major turning point in my craft journey as I start to explore and make the most of the opportunities offered to me as a result of my QEST Scholarship.”

- Greg Kent

“The Spirit of Things”, Collect 2025

The display, featuring Japanese artists and others that were sympathetic to Japanese aesthetics, was layered to resemble a collection accumulated over time. It offered a curated glimpse into the serene yet dynamic relationship between the makers, their materials, and the spaces they inhabit.Our stand’s curation centred on natural materials and these textures had a beautiful response to the sunlight.

A key part of the stand’s curation was a furniture collection byJames Trundle & Isobel Napier . This new body of work uses digital techniques to simulate the natural contours of the timber. This collection explores the interplay between the exacting nature of digital design and the organic, tactile qualities of natural materials.

YORIKO MURAYAMA

Japanese Glass Artist

Photography by Isobel Napier

TIMBER SOURCING

“Ahead of our showcase with Flow at Collect 2025, join us on a trip to the timber yard as we search for characterful boards from London trees, to make our new body of work”.

“At the heart of our craft is a profound respect for the timber we use. It forms the foundation of our work, with each piece shaped by the unique character and story embedded in the wood.

All the timber used within our pieces is sourced from Fallen and Felled, a London-based timber yard dedicated to rescuing trees from the incinerator. By choosing timber not grown for commercial purposes, we make a conscious effort to use resources that would be overlooked, allowing us to incorporate unique and distinctive wood varieties into our designs. This practice not only supports sustainability, but also enhances the character of our furniture. Our designs highlight the intrinsic beauty of these timbers, embracing their natural features—knots, splits, and irregularities included. By incorporating these characteristics as distinctive elements of our designs, we collaborate with the material, minimising unnecessary removal and reducing waste off-cuts to the absolute minimum.”

- James Trundle

Hammer & Hand

Drawn to finding character and a human-like semblance in inanimate objects, Ghanaian born silversmithFrancisca Onumah creates ambiguous vessels and jewellery that reflect vulnerabilities and strengths through their anthropomorphic forms. Working from sheet metal, she subtly layers different marks, patterns and textures by repeatedly hammering, fold forming and impressing textile patterns onto the surface of the metal. She tells Flow more about her techniques, inspirations and the forms she is most drawn to.

What draws you to the vessel form?

There’s something about the vessel, it’s such a recognisable and relatable form. In the vessel form I see different figurative aspects to it – features such as the body of the vessels, the feet, the mouth, can be translated in so many different ways. Some of my earlier work was inspired by different types of vessels, like marine vessels inspired from the Dockyards that I grew up by in Kent. I now make vessels inspired by the human form, which is a vessel in itself. There’s a really lovely connection we have with vessels that I enjoy, I always love watching people pick up and interact with the vessels the way they hold them. The forms as well as the textures really encourage that.

What inspires the patterns on the surfaces of your pieces?

I’ve always been inspired by textiles patterns and motifs. I particularly love looking at Ghanaian textiles, batik prints, Kente cloth and mud cloths. I bring these motifs and patterns into my pieces by creating pleats and folds in the surfaces as well as combining hammered textures with fabric textures taken from calico and tulle fabrics.

How do you develop your designs?

I tend to design as I’m making, I love drawing using different 2D media such as graphite pencils, pastels, ink. I find inspiration from old photographs of African villages, looking at the architecture, figures and textiles. I also love the work of sculptors such as Brancusi, Henry Moore and potters like Lucie Rie and Magdalene Odundo. I love the organic and figurative forms of these sculptors and makers.

I start off with initial rough sketches of different forms and work from there. I usually work from sheet metal, creating the surface textures with different mark making techniques, using textured hammers, and fold forming. I will then use the traditional silversmithing technique of raising to create the vessel forms. As I’m making, I’ll tend to combine different shapes and forms together to further develop the final form of the vessels.

The making process can be quite therapeutic. From the rhythmic noise of hammering – both in raising and in hammering the textures on to the surface – to the repetitive and slow process of folding individual pleats onto the surface.

What first drew you to silversmithing?

I have always been drawn to art and design, and knew from a young age that I would end up in a creative career. I initially wanted to study either interior design or architecture at university, however, after doing a foundation course at the University for the Creative Arts in Rochester (which is unfortunately now closed), I fell in love with contemporary art jewellery. I loved being able to make tangible objects and seeing the way sculptural objects interacted with the body.

I was first introduced to silversmithing on my BA at Birmingham City University’s prestigious School of Jewellery. My initial interest was in jewellery and adornment. The course was more focused on contemporary / art jewellery design, with a few short masterclasses in silversmithing. I became more and more interested in the skills of silversmithing in the second and third year of my BA course. I really enjoyed the physicality of silversmithing and the breadth of techniques you could use within it. I also loved the sculptural scope with silversmithing.

How does your work engage with or subvert these silversmithing traditions?

I enjoy using traditional silversmithing techniques such as raising, however I like to be quite intuitive with my making process. For example, I tend to hammer the textures onto the sheet metal before I raise the form, instead of doing this afterwards. I find that it gives a less uniform finish on the vessels and allows for the texture to be adapted in an organic way whilst in raising. Instead of using a raising hammer, I use a rawhide mallet that I’ve adjusted to have the shape of a raising hammer – this allows the marks that I’ve already put in to remain on the surface.

There’s a rich history silversmithing, especially in Sheffield, and I really appreciate the years of developing its different skills. Like most traditional crafts in the UK, the techniques aren’t being passed on to the next generation as thoroughly as it would have been in the past which is such a shame. And even though lot of the traditional techniques are still being used, silversmithing looks completely different from what it did 50, 30, even 20 years ago. I think it’s important for the next generation of makers to understand and use the traditional techniques and pass them on; however, tools and materials have changed, which means we adapt the way we make things. In the past, a lot of silversmiths worked for a big company, where they’d work on a specific element of a piece whilst making batches of the same pieces. They would be skilled in a very specific skill like tray sinking or spinning. Now, however, most of the piece would be made by an individual maker, who will then outsource very few elements to tradespeople.

Your forms could be seen as anthropomorphic and having ‘postures’ and conversations, is this something you intentionally seek to achieve?

I’m really drawn to the relationship between people and objects, the way in which people relate to and interact with objects. I’m particularly drawn to forms that have a vulnerability to them, the vulnerable postures and conversations are almost like the vessels are inviting you in and as if they have a history or story they want you to be drawn into. This links in with the ideas of imperfection and accepting the marks during the making process – these tell a story of the life that the vessel has lived whilst being made.

I make my vessels in groups and throughout the making process I sit them together as if they are having conversations between them, I look at the way they sit together. I’m reminded of familial connections that I hold dear to me. I come from a big Ghanaian family and the act of family, close and extended, is a very ritualistic act. I visited Ghana for the first time in 20 years last year. Throughout my trip I found that families gathering together, eating together and sharing stories is a very central value that we as Ghanaians hold.

What interests you in ideas of imperfection/perfection?

I always found the Japanese theory of Wabi-Sabi (acceptance of imperfections and transience) really interesting. The idea that an object in its brokenness can be made beautiful through its so-called imperfections.

When I was studying Jewellery and silversmithing at University, there was a lot of focus, especially in silversmithing, on creating perfectly made pieces. This tends to mean neat and perfectly soldered seams, or polished surfaces. I found that quite constraining and found that the more I focused on the idea of perfection, the less creative I was in making. So I used that as a starting point for my MA project, looking at the imperfections in creating a vessel, highlighting the seams and the solder joins, purposely creating bruises and scuffed marks in the surfaces of my pieces. This led me to seeing a connection with the vessel and the human form and led me to develop the more anthropomorphic characteristics of my current work.

I used to be a perfectionist when it came to my art and I would rip out pages in sketch books if they weren't perfect. I would be very particular and spend way too long making a piece of art. This exploration of Wabi-Sabi made me address the issue of perfectionism within myself and has made me more creative in my practice.

Francisca Onumah has been the recipient of the prestigious Jerwood Prize and has work in notable collections including The V&A, The Walker Art Gallery, Sheffield Museums and Sheffield Assay Office.

Interview by Alina Young

A New Collection by Kerry Seaton

An emphasis on shape is integral to her approach, she is committed to the quality of craftsmanship and is sensitive to the precious metals in which she works; She creates jewellery with longevity: to be worn in rather than worn out. She concentrates on timeless quality and a sense of stillness.

Kerry Seaton on her practice :

"An understated form of beauty, a quality refinement masked by rustic simplicity."

Photography by Isobel Napier

A Silver Anniversary | Sparkling Wine Tasting with Adi Toch & Jochen Holz

This week we celebrated our Silver Anniversary with an English Sparkling Wine tasting - tasting from bespoke silver vessels made by metal artist Adi Toch, and a special collection of champagne flutes by glass artist Jochen Holz. Thank you to Alfie Glasser of Liberty Wines, for joining us for the evening and talking us through the flourishing world of English sparkling wine.

Aflie said of the experience:

“After exploring the historical context and potential impact of drinking wine out of silver vessels, I concluded that very little would happen to the wines.

I was pleasantly surprised to find that the wine tasted from the inert glass vessel, seemed to have more body and a riper fruit character.

What was also surprising, was that when tasting the wines from Adi’s goblets, the silver accentuated the Langham’s expression of site: I truly could taste the Jurassic Coastline. The wine felt clean, pure, and vibrant, highlighting the briny minerality of this coastal wine.”

Adi Toch :

“As an artist, vessels and containers offer an innate method of communication for me, conveying a multiplicity of narratives including gathering, holding or carrying.”

Jochen Holz :

“This set of hand blown, lampwork glassware aims to bring together a spontaneous & improvisational flow to the making.”

Photography by Isobel Napier

Art & Flowers | Flower Arranging with Frida Kim

Working with glass and ceramic vessels from Flow’s collection, as well as personal pieces that our collectors brought in from home, Frida showed us how to bring them to life with flowers.

Frida Kim

“Design, beauty, art, nature and fashion have always inspired me. For many years I ran my own custom jewellery business in Seoul. After moving to London I fell in love with English winter gardens and the beauty of English Flowers. My curiosity and passion took over my life. I have had the fortune to learn from great teachers who shared their wisdom and skills with me.”

Philosophy

“Each pure in its imperfection and alluring in its beauty, flowers carry stories to be told. It is these stories that captivate me as a florist. I am driven to give flowers a voice and make their stories heard. Taken by the ephemeral and delicate grace of each flower, I become a vessel to unite their elegance and wild nature. I strive to do each story justice by the meticulous choice and combination of colours, creating depth and warmth though the tones and textures of each petal, leaf and stem. Each flower and foliage are given their own space – a balance that allows each to shine without outshining the others. In their togetherness, flowers become the words and emotions to their own story. Just as it is at the hands of the florist that flowers gain meaning, it is through the careful arrangement of flowers that I expresse my life. In the spaces between the petals you will discover my story.”

- Frida Kim

Photography by Lisa Stockham

Autumn Harvest in BOSEONG - Korean Tea Tasting

To initiate the start of their exhibition with Flow, South Korean potters Seong-Il Hong & Hye-Jin Lee lead a Korean tea tasting featuring their handmade made tea ware.

Seong-Il and his wife Hye-Jin are based in Boseong in the south-west of South Korea, where most of the country’s tea is grown. The studio they run together looks out onto the local valley and tea plantations. They bought local teas as well, water and ingredients to recreate at Flow the feeling their home and studio.

Beauty in Everyday Moments

“Unlike pure art, crafts serve as a medium for communication, enabling people to connect with one another. I discovered that teawares, in particular, are captivating because they allow individuals to enjoy a more leisurely and beautiful aesthetic experience in their daily lives.

While there are mass-produced wares that are widely used, the world of art I pursue focuses on creating delicate and intricate pieces with more care. I want those who view my work to find their own aesthetic sense and meaning in it, allowing the pieces to remain significant in their lives for a long time.

Bridging the gap between “good-looking” pottery and “good-to-use” pottery, teaware is a craft that neither overflows nor excludes its functional or aesthetic elements, but is special to everyone. This balance is at the heart of my creations.

This is my approach to creating pottery, and I hope that those who encounter my work will feel its essence. As the saying goes, ‘Big changes start from small things,’ I will continue to strive to create works that remain a friendly presence in our ever-changing lives.”

- Seong-Il Hong

Videography by @monstar.play

Photography by @monstar.play & Isobel Napier

New Throws by Catarina Riccabona

"I enjoy the flexibility and the spontaneous changes that are possible when weaving by hand. I observe and constantly re-assess how these weave structures materialise in the fabric during weaving."

Catarina Riccabona is a hand-weaver creating unique pieces, mainly throws and, more recently, wall hangings. “For me, the process of hand-weaving is endlessly intriguing and keeps informing and pushing my work. Its slow-paced, contemplative nature and the possibility to make changes spontaneously offer a dimension that goes beyond the mere production of a piece.”

This process is key for creating her designs. “When I start a piece, I often don’t know what it will look like finished. I work at the loom in a spontaneous, intuitive manner thereby simultaneously creating and executing ideas. Each piece is a unique arrangement of elements and a new composition.”

Catarina’s hand-woven throws are made with a blend of materials; the warp is natural white (unbleached) alpaca wool, with a small amount of natural white alpaca. This gives the throws an unmatched softness and tactility. The colourful wefts use recycled linens and cottons, as well as wools and natural white alpaca.

"My practice is based on environmental values. I often use unbleached and undyed linen in my warps. My choice of weft yarns is limited to naturally eco-friendly yarns like linen, hemp, undyed or plant-dyed wools and undyed alpaca from the UK. If I use any other types of yarn, like cotton, it comes in the form of a second-hand or recycled yarn. For colour, I use plant-dyed wool by a natural dyer from Finland, second-hand yarns or recycled yarns from a British company who process industrial surplus into new yarns."

- Catarina Riccabona

Studio Photographs by Yuki Sugiura

An Interview with Michèle Oberdieck

What is your process for developing designs?

I start by sketching and painting from found objects, mainly from nature, redrawing and painting them until I feel they’re right.

I then model them in clay to see the actual depth the piece might involve.

It’s better to have a 3D visualisation for a form before going into the hot shop as once we start working with hot glass, decisions have to be made very quickly.

There’s no time to pause and rethink a piece. We work in the moment.

Each step of planning and making involves an editing phase. Like the material, I tend to work quite fluidly, changing certain perspectives when they become apparent.

Could you tell us about the relationship between your design process and making the works in the hot shop?

With the slower design process, I digest the idea over time.

The immediacy of making in the hot shop is more instinctual, and intrinsic.

Without one you couldn’t have the other.

How do your ideas for colours translate to the finished piece?

I work quite a bit with watercolour paint as it has an immediacy which translates well with blown glass. I look at a lot of fine arts and painting.

I then match glass colours to my sketches. Coloured glass, however, contains metal oxides which react differently under different temperatures. I always sample my glass pieces first before executing them.

I find it quite thrilling when another colour appears due to the reactions of two colours together, which may then change my original ideas for a piece.

Could you tell us about the techniques you use for creating colour and shaping the pieces?

I use rods of coloured glass which I then cut into pieces, depending on the intensity I’m after. These are heated up in the furnace and coated with a gather or layer of clear glass, often two layers. As the form is blown larger, each colour expands or contracts depending on how soft or hard the colour is. Unlike other materials, with glass the form and colour evolve simultaneously.

I hand-shape the pieces using wads of damp newspaper to protect my hands against the heat. It feels more personal shaping the glass forms this way rather than using moulds, as I feel it creates more character.

How do you find inspiration for the fluid, asymmetrical forms of your pieces?

My inspiration for the asymmetrical forms is mainly found in nature.

I’m always surprised how much weather, sea and other natural elements shape natural material.

While walking along Fossil Bay near Margate, I was amazed at how many miniature Henry Moore’s and Jean Arp sculptures I could see in the stones.

How do their forms interact with colour?

Colour has always been a major source for me.

There’s an infinite number of gradations and tones when looking at a water source or the sky, or the way colours bleed and fade when plant life starts to decay.

The forms interact with colour by the way light reflects across the shape and illuminates it.

Light with colour creates another dimension.

Light is integral to your work – do you design with light in mind? What do you find interesting about the interaction of light with the finished piece?

Light and glass are the perfect marriage. Light is integral to glass and has the capacity to change it both drastically and minimally. It compliments glass to no end.

What’s wonderful about how a glass object is the way it can change throughout the day.

From morning to dusk, the same object can look completely different depending on the light source.

What looks opaque can look transparent, what appears dark and all one tone, with sunlight a completely different hue can appear.

Interview by Alina Young. Flow photography by Isobel Napier

Studio photography by Sylvain Deleu

Summer Shelves

Featuring ceramics by Cécile Daladier & Derek Wilson; glass by Celia Dowson, and baskets by Shannon Clegg & Lizzie Kimbley, among others.

This curated collection celebrates the beauty and diversity of natural colours and textures. By selecting pieces that showcase the intricate hues found in nature, the selection appeals to the senses.

At the centre of this curation are smooth ceramic and glass surfaces, which provide a clarity and contrast to the more rugged textures of other natural materials.

The collection includes textured pieces crafted from dried flowers and woven fibers. These tactile elements and patterns bring a sense of warmth and earthiness.

Together, they form a collection that reflects summer’s diversity and the pleasure of combining contrasting elements.

Photography by Isobel Napier

An Interview with Akiko Hirai

Rin-ne Tensho 輪廻転生

–n. the cycles of reincarnation

rin-ne: circle, a wheel revolving, an endless cycle

tensho: transmigration of life, birth, death

From Japanese Buddhism

Whilst preparing her new solo exhibition for Flow, Akiko Hirai has been inspired by the changing seasons on her daily walk to the studio. "Lately, it rains a lot, and the green comes out. So, it's water and colour. On the surface of these pots, there is texture - that is rain. There is a little green on the outside. These are the themes of the faceted pieces. The dark one is more towards the night. But recently, when I go home it's still bright - so I only made one in this collection. When it's brighter outside, I find myself making brighter things. It comes naturally with handmade things, they reflect what you see." “Between table-top and art, castle and hut, the natural and the man-made, the beautiful and the ugly, the fragile and the coarse ... just in-between.”

Akiko's title for the show, "Rin-ne Tensho 輪廻転生", relates to reincarnation and the cycles of life. Alongside her inspiration from the changing seasons, she relates to a sense of circularity in her process - the cyclical nature of accumulation and disintegration."In the plates, it's the thickness of the slip underneath; under the white slip, which crackles, it’s dark. You rotate the plate after applying it, to move the slip around; where it’s the thicker part, it’s the bigger crack, where it’s the thinner part, it’s the finer crack. Where it’s thinly applied and you can see more green, you can see things growing. This is accumulation. The Moon Jar is also about many things accumulated, growing… the very quiet ones too. When the accumulation gets too much, it comes off. It’s the natural cycle. It’s circulating. In a word, this is Rin-ne Tensho, reincarnation."

Akiko Hirai has shown with Flow Gallery for over 15 years, and so we are delighted to be hosting this solo exhibition during our 25th anniversary celebrations.

Interview & Text by Alina YoungPhotography by Isobel Napier